My First Ever ICPC Regionals Experience!

This past weekend, I attended my first ever ICPC regionals! It was an incredibly fun and enlightening experience for me, so I’d like to share with you some takeaways I had.

First, let me provide a bit of background, since I think I’ve only referred to myself by handle on my blog so far. My name is Max, and I’m a first year CS major at Georgia Tech. My teammates for this regional were Arvind and Jeffrey. We were team “Acceptable” at the 2021 Southeast US Regional.

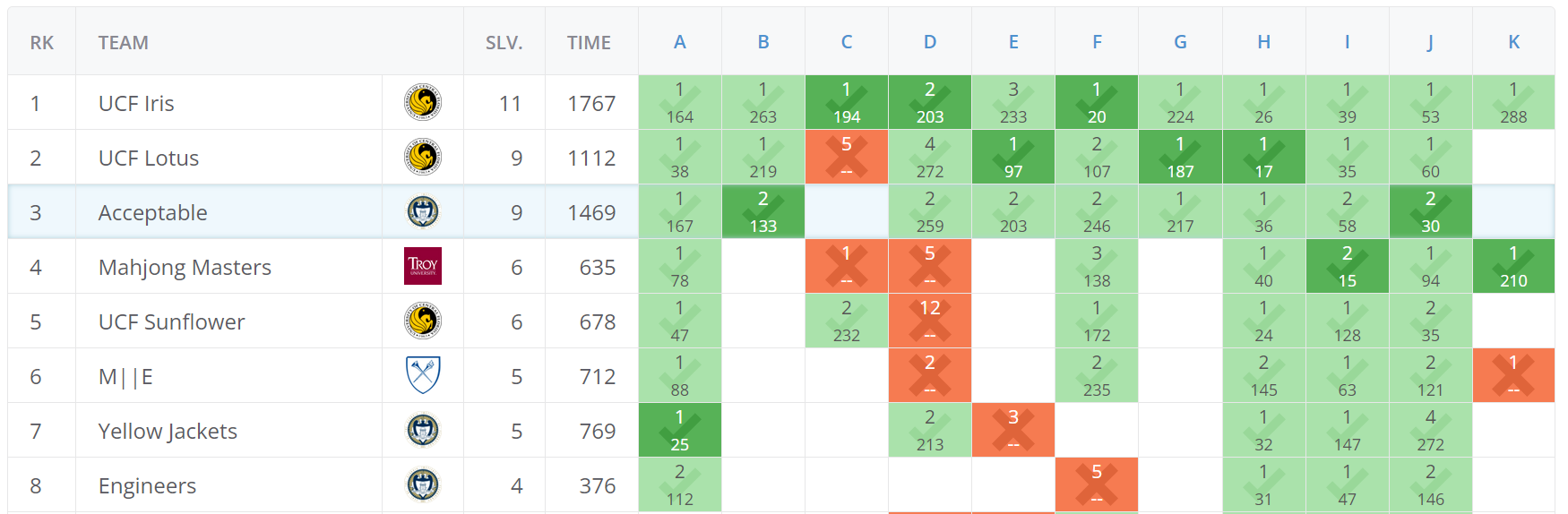

We ranked 3rd overall, or 2nd after removing duplicate schools, which qualifies us for the NAC.

In the following spoiler, I’ve put a play-by-play of how our contest went by the hour, reconstructed with help of our submission history, scoreboard, and my personal memory. The exact times might be slightly off because it was extremely hectic to keep track of all these things during the actual contest. This play-by-play is also only from my perspective; I might not mention what my teammates were working on at a given time because I wasn’t paying attention to what they’re doing.

Play-by-play

So as you can see on the scoreboard, the two teams that beat us were both from UCF. Going into this contest, our coach chenjb had already warned us that UCF would be the major threat in this competition and they were extremely good at speedforces, so we knew we had our work cut out for us.

The contest begins. Arvind and Jeffrey start flipping through the problems while I type out our template and set up an alias command for compiling with warning flags. Our first impression of the problemset was that it didn’t look hard enough to not be speedforces, so we knew we needed a strong pace to have a chance of winning.

About 5 or so minutes in, Jeffrey tells me problem F looks like an easy DP. I quickly skim problem F and confirm that it indeed looks like an easy DP. I code the most naive shit possible and submit it at 8 minutes in:

1

2

3

4

for (int i=0; i<k-1; i++)

for (auto [x, y] : spots[i])

for (auto [a, b] : spots[i+1])

dp[a][b] = min(dp[a][b], dp[x][y] + min((x - a) * (x - a), (y - b) * (y - b)));

We submit and eagerly await the verdict, hoping that we got first blood on this contest. And we’re greeted with… time limit exceeded? I look over what I submitted and facepalm: our solution was $\mathcal O(n^4)$ when $n \leq 500$! Somehow, I had convinced myself our solution was amortized $\mathcal O(n^3)$ or something when I coded it, but no, it’s $\mathcal O(n^4)$ when there are lots of points in two consecutive layers. I rethink the details and come up a horrible solution using linesweep and maintaining prefix/suffix minimums. If you know this problem, you’ll know this is not the intended solution, and there’s a much, much, much easier solution that can be coded in less than 10 lines. But anyways, for now the linesweep bash solution is the only one I have in mind, and I tell my teammates it’ll take a while to implement, so we put problem F aside for now.

The next problem we attempt is J, which Arvind goes to code. He finishes the code extremely quickly and we submit at the 12 minute mark. We eagerly await our verdict and get… wrong answer? We reread the problem and facepalm again: we misread the problem! The problem isn’t asking if adjacent vertices in the tree are more than distance 3 apart in the permutation. It’s asking if adjacent vertices in the permutation are more than distance 3 apart in the tree!

At this point, we’re down bad. It hasn’t even been 30 minutes in and we’re already losing on penalty to UCF with no ACs yet. We think for a bit longer, but we don’t see how to take advantage of it being distance 3 or less. The only solution we can think of is brainless LCA bash that would work for any distance $k$ apart. I decide to just go ahead and implement it.

I hammer out a solution using binary lifting to find the LCA, run it on samples, and it… crashes. I’m so confused. I’ve literally never messed up binary lifting in practice before, but it appears there’s a first time for everything. If only that first time wasn’t at ICPC regionals :/ . After staring at my code and commenting out parts of the code to find the location of the crash, I still can’t find the bug. Jeffrey is also ready to code problem H, so I print my code and pass the computer over to him.

Staring at my code on paper still doesn’t help. Luckily, Arvind also takes a look at the code and points out my silly mistake: in my DFS method, I referenced the wrong variable, p instead of u, for a certain line. Ahhhhhhhh!!! I quickly make the edit on the computer and submit to claim our first AC 30 minutes into the contest. But this first mistake would be a sign. Because you can bet this was certainly not the last mistake I made on this contest, but just the first of many…

Shortly after our AC on J, Jeffrey completes his code for H and claims AC on first submit. Nice! The next problem he attempts to code is I. After one wrong submit and a quick bug fix, we claim AC on problem I.

I should also note that sometime in the midst of all this chaos, we implemented problem A. I don’t remember if this was before or after we got problem I (I think it was after). What I do remember is that we saw on the scoreboard that several teams had solved problem A, so we figured it couldn’t be that hard. And indeed, upon reading we immediately thought of bitmask DP, which is the intended solution for this problem. I came up with some formulas and coded problem A. It worked on the first two samples, but to my dismay it failed on the third. Problem A will end up being an on and off thing that we think about whenever the computer was free, and it will serve as a bottleneck for the next 2 hours…

At this time, we also decide to code my linesweep bash idea for F, since the computer was available. Honestly, with my track record on this contest so far, I should have been banned from coding. I implement F, run it on samples, and what a surprise, I fail the second sample. LOL. I print the code and stare at it while contemplating life.

Jeffrey now codes problem B. He asks me if we have a modint template we can use, and I attempt to code one for him to use. Unfortunately, my modint template doesn’t compile because of weird C++ const lvalue/rvalue crap (seriously, why am I still coding in this contest?), so we give up and just manually mod after each intermediate calculation. He submits at almost 2 hours into the contest and gets… time limit exceeded? We reread the problem and realize $n \leq 10^{12}$, and Jeffrey was trying to code an unoptimized version of his idea that ran in $\mathcal O(n)$. I notice that the linear time part of his code:

1

2

3

4

for(int x=1;x<=n;x++) {

cos[x] = (cos[x-1]*cos[0]-sin[x-1]*sin[0])%mod;

sin[x] = (sin[x-1]*cos[0]+sin[0]*cos[x-1])%mod;

}

looks like a linear transformation. So it can be optimized with matrix exponentiation. I add matrix exponentiation to his code and resubmit, giving us AC on problem B 2 hours and 13 minutes into the contest (and first solve on B!). We’re finally starting to bounce back a little, albeit we’re still missing some easier problems (according to the scoreboard) such as problem A.

The next target is problem E. Arvind tries implementing a backtracking solution because he guesses there might be good properties of the problem that allows the backtracking to run faster. We also write a generator to create some large cases which seem to verify this claim. However, our claim turned out to be false, as we got time limit exceeded on submit.

A little after this, Arvind comes up with an alternative set of formulas for implementing the transitions in problem A. He goes ahead and implements it, and gets AC first try. Nice. Still don’t know why my formulas are wrong, but I guess that works.

Shortly after that, I notice we can use 2-sat to solve problem E. Specifically, KACTL’s version of 2-sat, which we have in our team reference document, has a convenient function atMostOne that does exactly what we want. And to find the lexicographically smallest solution, we can just try placing characters one at a time and repeatedly run the 2-sat algorithm after each character placed. I code this solution and thankfully get AC first try (given my ratio of correct to incorrect code written on this contest, I might have actually lost my mind if I wrote yet another buggy code). And shortly after that, Arvind codes his idea for problem G and also gets AC on first try! Now at 7 problems 3 hours and 30 minutes into the contest, we were finally catching up to the front of the leaderboard.

After all of this, we finally knock out problem F. I realize that my linesweep bash idea was wrong because I wrongly assumed I could use two-pointers in one section when I actually couldn’t. And we also realize the much easier intended solution at this time: for each cell, just brute force over the $x$ or $y$ value that we transition from in the previous layer and take the minimum of all cells in the previous layer with that $x$ or $y$ value. This works because the cost function for moving is a minimum of $x$ and $y$, so any “wrong” transitions we considered won’t be optimal anyways. The code is super concise and clearly runs in $\mathcal O(n^3)$. We code it up and claim AC 4 hours in. And shortly after this, Jeffrey codes and claims AC on problem D.

Now, we enter the final 30 minutes of the contest. Our hopes are to get one more problem, because we were certainly losing on penalty among teams with 9 solves. After some pondering about problem C, we figure maybe backtracking will work because the problem guarantees there exists exactly one solution, so the search space is likely much smaller than the naive bound of $2^{n^2}$. I code up a recursive backtracking solution and it… doesn’t work on samples. I was unable to debug it successfully during contest, likely because I was panicking due to there being little time left. The solution did pass when I recoded it again in upsolving, so my guess is I just made a typo during the onsite :/ .

With 10 minutes left, Jeffrey tells me he has the solution to problem K. But it was unfortunately too late, and we could not finish our code before the end of the contest. And even when we submitted immediately after the end of the contest, we got WA, so we would have needed way more time. The contest was over.

Hopefully that play-by-play wasn’t too dry to read (or if you didn’t read it, that’s ok too). Anyways, here are some of the takeaways I have from this experience:

1. I’ve forgotten how great in-person events are.

I’m opening with this point because I want to make clear that despite my frustration expressed at some moments in the play-by-play, I genuinely had fun at regionals. I complain because this wouldn’t be a smax post-contest reflection post without some form of complaining, and because I’m generally quite critical of myself, but I still want the main takeaway from this post to be how great my experience was.

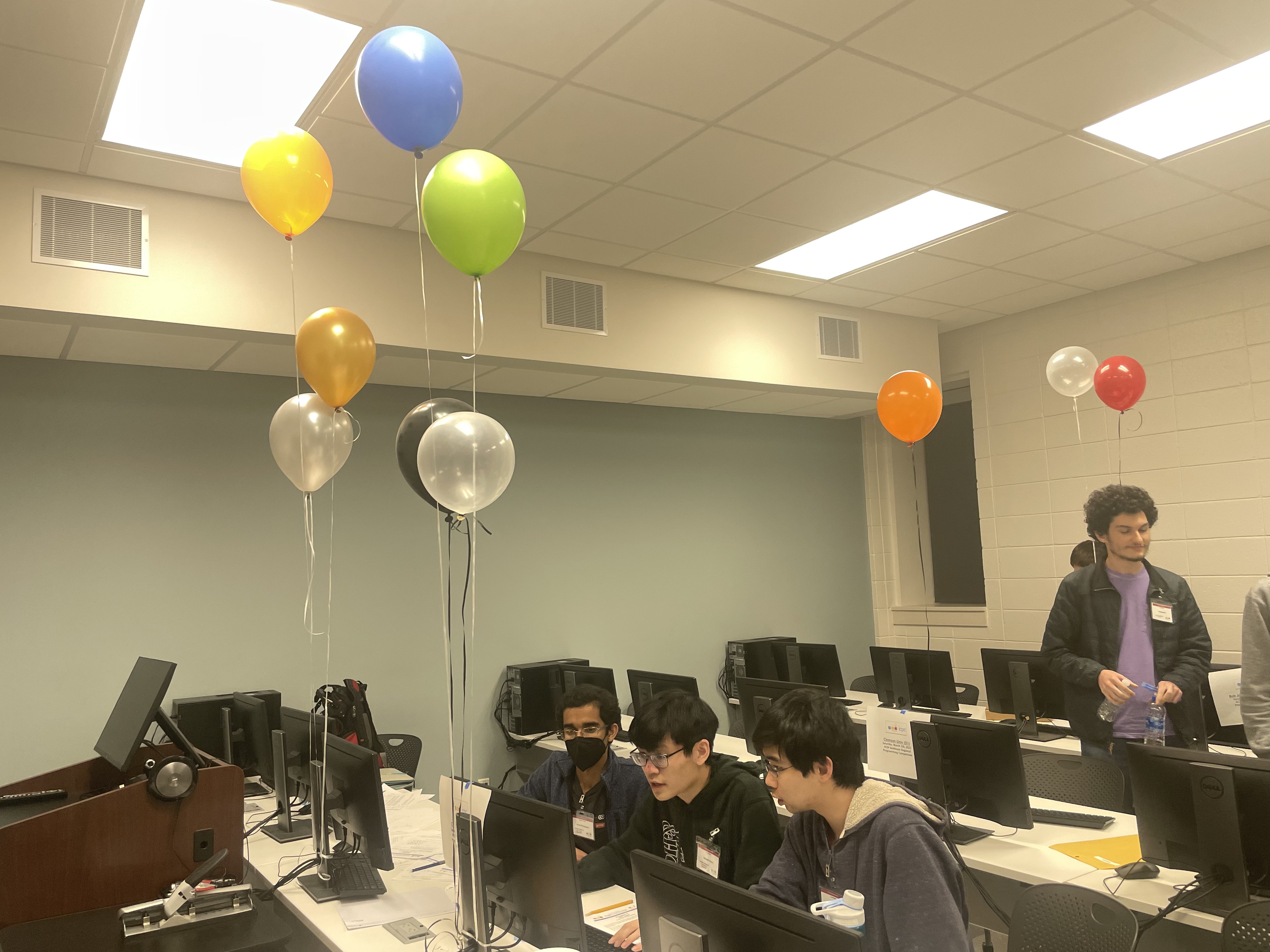

The vast majority of CP competitions such as Codeforces, AtCoder, or even many team competitions I did in high school, are online. I sit in my room and log onto my computer to compete. In the case of a team competition, I join a Discord call to coordinate with my friends. But the atmosphere is very different when you’re actually sitting in a room with other competitors and hearing different teams discuss amongst themselves. And on our site, the runners bring a balloon to your table whenever you get AC on a problem, which adds to the hype (though I will say I got super psyched out at the beginning because the div 2 teams in our room were accruing balloons at a super fast rate near the beginning of the contest). It’s just that much more fun and satisfying when you see a physical reward for your ACs. I have no doubt it will be extremely hype to attend NAC in-person and sit in the same auditorium as the strongest CPers from across North America.

And while we’re on the topic of positives, I’ll say that while I didn’t get the chance to properly appreciate it in contest, problem K was a really fun problem to upsolve. If you want to solve it yourself, then as a hint,

2. I didn’t realize how reliant I was on my own setup.

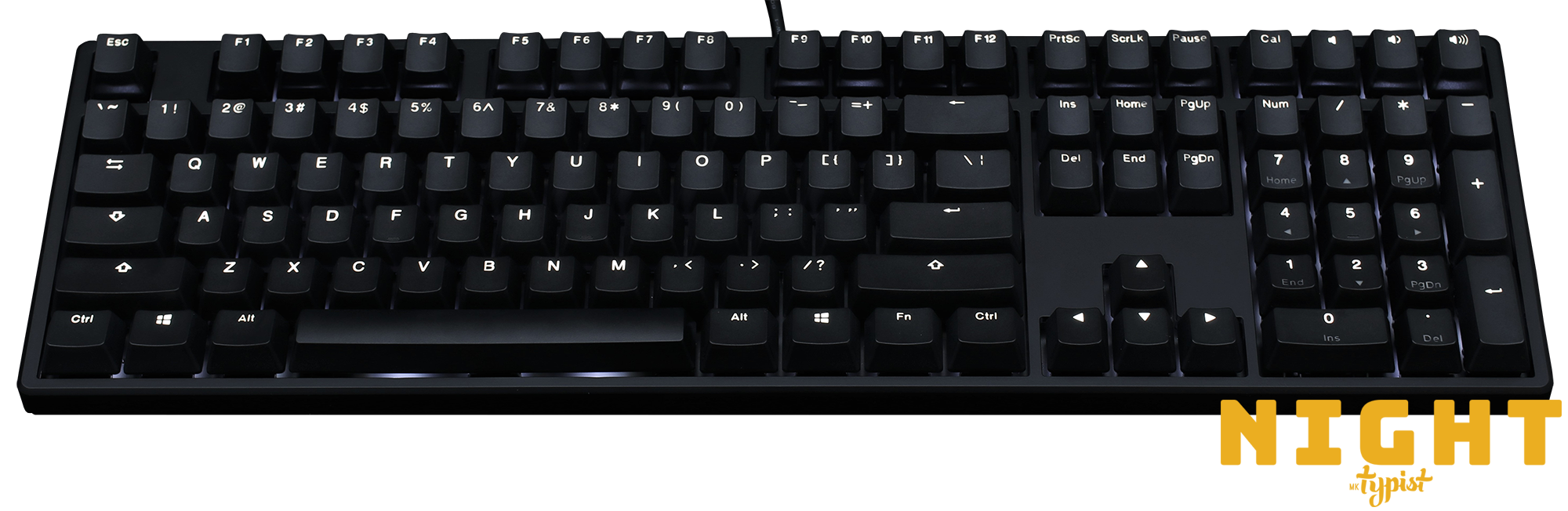

At regionals, our team used VSCode, but the setup was very different from the VSCode setup we used in practice. You can’t access the internet to install extensions on VSCode at regionals, so VSCode simply operated as a glorified text editor for our use case. The lack of a linter meant I had no idea if my code would compile until I ran the compilation command, so the number of uncaught typos I made definitely increased. Also, the number of times I hit “ctrl + Q” out of habit and accidentally closed the VSCode window (because on my personal setup I have “ctrl + Q” mapped to something else) was stupidly high. Finally, the keyboard they gave us at regionals was a big keyboard with the arrow keys on the far right. So something like the image below:

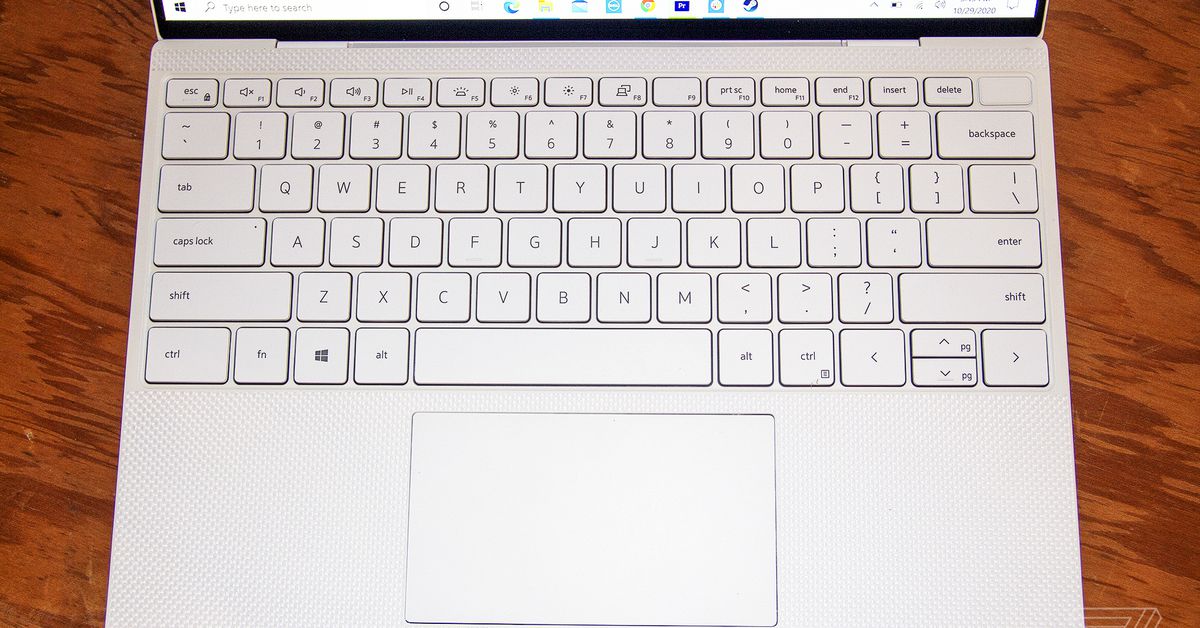

You might wonder what difference this makes. Well, the keyboard I personally use on both my laptop and my PC is a more concise keyboard with the arrow keys directly underneath the “shift” key:

In this keyboard, the arrow keys can be reached without moving my right hand, while I can’t do that in the larger keyboard.

Yes, that’s right. I use the arrow keys when coding. Instead of closing the right parenthesis by actually typing it, I use the arrow keys and rely on the autocomplete in my code editor to fill in the right parenthesis. In my defense, it’s unnatural for me to type the right parenthesis when I already see it autocompleted on the screen, but this difference definitely messed with me during regionals and made even typing a simple for loop a much slower procedure. Of course, I’m not saying that we would have been significantly faster if I typed faster, because the bottleneck for our slow performance was still buggy code. It’s just a small difference on top of many mistakes I was already making.

3. I need to be more consistent.

It would be disingenuous for me to say “oh if I didn’t make a typo on J and if I didn’t code A wrong and if I didn’t code F wrong and if I was basically a perfect human being, we would have won.” Committing mistakes and debugging are all part of the game, and the team that’s best able to adapt and mitigate the damage of these mistakes is the one that comes out on top. Looking at the scoreboard, UCF also made wrong submits, which means their best case performance would have smoked our best case performance regardless.

The issue is that I’m really bad at recovering from a rough start. I described a similar pitfall in my reflection post in January, where I never recovered from a rough start on Global Round 15 and lost 139 rating points. I think in this regionals, I also suffered from a similar issue where previous mistakes snowballed and made me more prone to committing future mistakes. If you didn’t know me and judged my behavior this round, you would have thought I was a candidate master.

One way to alleviate this is to be more consistent in the first place. Reach a point where even my worst case performance is somewhat acceptable. I think this is an attribute that people overlook when discussing how to get better. If you look at performances of the top 10 competitors on CF, you’ll notice that they hit consist LGM performance not just every once in a while, but almost every single time. And even if they brick on an early problem, they can usually salvage their performance with a solve on a harder problem to compensate, so their losses are never that devastating. Personally, I’ve gotten IGM performances before, but an ideal state would be to be able to hit IGM performances consistently, which will be my next goal.

Another way is to just get better at keeping my cool. Don’t let early mistakes affect the rest of the contest. This is of course easier said than done, but it’s a skill that would benefit me not just in CP, but in life.

Congrats for making it this far! If you’re still here, here are some pics taken at the event. Cheers, and hopefully we’ll do better at the NAC!

Clowning in 4K

Awards ceremony! I am second from the left, the one wearing the dark green hoodie.

School picture! Georgia Tech sent 6 teams in total.

Productive use of balloons :)

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops