A Competitive Winter Break

Happy new year! It’s been a minute since I last posted, but here’s my first post of 2022. I was trying to go for a title similar to Petr’s blog posts with the adjective + “week” format, but it doesn’t really sound that good now that I’ve typed it out.

Firstly, I must apologize that the tier list I mentioned at the end of the last post is not ready yet. I originally planned on working on that over winter break, but ended up putting it off and falling back on unproductive habits instead.

For the time being, I figured I’d write an update post about CP competitions I did over winter break, because I had some more time to participate in several of them.

Rated Codeforces

Ever since I first hit red in September, I’ve taken a hiatus from competing in rated contests. But I have to say, playing out of competition just didn’t hit the same. Aside from it out of competition contests being div 2 instead of div 1, competing unrated just feels more low stake and not as fun, so it was refreshing to compete in rated contests again over break.

I did three rated contests over break. The first was Global Round 18, where I paid an unexpected visit to master rating again 😬.

My contest experience consisted of a lot of hopping around between problems and just not seeing simple observations (when I say simple, I mean that based on my average performances, I would typically be able to find observations of this difficulty). I’ll include a retelling of my contest performance in a spoiler below:

The Story

Problem A and B were quick solves. I got the right ideas and submitted them relatively quickly. Next is problem C. On first read, I misunderstood the problem as only flipping adjacent candles instead of all other candles, because problem C reminded me of a different problem I saw before involving flipping adjacent candles. After working through the samples and realizing I misunderstood the problem, I switch to thinking about flipping all candles. I play with the samples and other small cases for a while, but no obvious pattern emerges. A significant amount of time passes without me solving it, and I decide I need to skip C for now to salvage my performance.

I open problem D. I get the observation about the parity of the bit count also being xor’ed pretty quickly, which means I only need to assign the unassigned edges 0 or 1. But I’m stuck on how to recover the answer. Again, I think about different ways of assigning, including some weird greedies, but nothing concrete comes to mind.

At this point, my morale and self-confidence aren’t exactly high, because I’ve just bricked on two early problems and am on track to getting specialist performance if another problem doesn’t get solved soon. I could move onto E, but the solve counts weren’t giving me any confidence that E was any easier than C or D. I also did a quick sweep through the entire problem set to see if there was some data structure problem I could knock out instead, but there didn’t appear to be any (yes, I later found out that problem G was general matching and problem H was a well-known flow problem, but I’m not too familiar with flows and matchings).

So I return to problem C. I finally come up with the following idea: if I form pairs between the characters at the same indices in the two strings, then only the count of 00, 01, 10, and 11 pairs matter and not the exact positions they’re at. So if I compress the string into a 2x2 frequency table, maybe I could do BFS on this state graph. But the number of states appeared huge, so I made another observation that would turn out to be wrong: I thought maybe we could cap the frequency table values at just 2 or 3 to reduce the number of states, because all of the pairs except for the one you’re operating on will flip. However, a wrong answer on pretest 2 disproved that claim. I code up a generator for a stress test because there’s not much else I can do, and I find that even when I increase the cap to 5 or 10, the solution is still wrong. However, I notice something strange as I increase the bounds: the naive BFS with no cap still runs fast even for $n = 10^5$. With no better options left, I submit the naive BFS, and to my surprise it passes pretests! At this stage, I was certain there might be some countertest that could fail my solution, and I was just hoping problemsetters would miss that case in the systests. I later found out that such a countertest doesn’t exist, because you can prove the BFS solution runs in $\mathcal O(n)$.

Finally, I return to problem D. After more thinking and still no concrete ideas on how to recover the answer, I attempt to cheese the problem with hill climbing. Unfortunately for me, the performance of hill climbing on this problem is really bad, to the point where it doesn’t even consistently get the samples right. I also read E in the middle of doing this, but at this point I have little motivation left to think properly about yet another greedy problem that I’ll likely miss the key insight for. And so the contest ends, and I’m left with the largest rating drop I’ve ever received.

If I were to reflect on my performance, I’d say my biggest mistake was getting tilted. I actually thought I’d gotten over that since my div 2 days, as I’ve gotten good at skipping problems. For example, I’ve had two performances (ex. 1 and ex. 2) in the past that could have been much worse but were somewhat salvaged by me skipping a problem I was bricking on. But bricking on not one, but two problems in a row was just too frustrating, and once I got annoyed it only went downhill from there.

Next was Goodbye 2021, which definitely went much better than Global Round 18.

No funny business happened this time. I got the right observations on the early problems and rolled through them quickly enough to get IGM performance despite not solving any of the GM+ difficulty problems. I did get one wrong submission due to integer overflow on problem E, which cost me roughly 20 places. Just speedforces things 😩.

To explain the -10 penalty on problem F, that was because I tried to cheese the problem with hill climbing again after not being able to think of a proper solution. It looked more promising than problem D from last round as the bounds were much smaller and I got to pretest 7, but I could not get it to work before the contest ended. As a side note, I’m annoyed I didn’t get the intended solution because the intended solution only had one observation: the “all colors pairwise different or equal” condition was equivalent to the colors summing to 0 mod 3. After that, you just turn each triangle in the graph into an equation and plug into Gaussian elimination. I also learned my Gaussian elimination library code was objectively worse than everyone else’s as my practice submission got uphacked.

The last Codeforces contest I did was Hello 2022.

Despite getting back to GM, this was an extremely frustrating performance for me because of one reason: my submission to problem G was one typo away from AC.

Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!!!

To clarify what happened: I made my first submission to G at 2 hours and 5 minutes. I’m greeted with a wrong answer on pretest 2. At this point, there are less than 10 minutes left in the contest, and I panicked because there’s like no time left to debug. I quickly rethink through my idea again and comb through my code, and I see no issues. At this point, I decide to stress test, which in hindsight was a fatal mistake. Stress testing takes too long. I would have to write a generator and a naive solution, and after finding the countercase I would have to add debug statements to my code and pinpoint where the countercase is tripping me up. Indeed, by the time I find the countercase via stress testing, there’s like 1 minute left and I’m unable to debug in time. What I should have done is just try to find the bug by inspection. Meticulously read each line and try to spot the bug, because that was the only chance I’d be able to debug in time.

This mistake was frustrating because I missed out on what could have been one of my best performances, and I missed out on solving a 3000+ rated problem in contest for the first time. I realize these are completely arbitrary milestones I’ve set for myself, but it still feels bad. I attribute this mistake to making a poor decision under pressure. I think going for G instead of F was the right call, because I heard F was a tedious casework greedy while G was much cleaner, and my mistake was trying to stress test in under 10 minutes.

Also, I don’t have much right to complain about this performance anyways, because I still went positive and it definitely could have gone much worse. For instance, I was lucky I got the hit-or-miss observation on D quickly, and on a different day it could have easily been another Global Round 18 situation.

Advent of Code

Advent of Code was running last month, and I was curious why so many good CP’ers were doing it. So I decided to give it a try. After following along for a few days, I concluded that I simply wasn’t the intended audience for these problems. From a CP standpoint, there were no interesting problems; almost every problem was solved with some form of brute force or “translate the problem statement to code.” I guess day 8’s second star was a nice ad hoc task where you had to deduce the digits from the set of segments turned on. But for the most part, the problem statements were overly wordy and complex, and half the challenge was understanding what the freaking problem was.

I’m sorry, but after seeing day 19 was yet another brute force problem, I couldn’t do these anymore.

And just to make sure I wasn’t missing out on elegant solutions, I checked the AoC subreddit, where I found out the average software developer loves brute force and finds it highly stimulating and engaging. Take day 16 for example, where the entire challenge was parsing the infinitely long problem statement and translating the procedure to code. Apparently that was one of the subreddit’s favorite problems. To be clear, I’m not saying these people’s opinions are wrong. I’m just amused at the difference in opinion. If you enjoyed the AoC tasks, more power to you, because having fun is the most important part of any programming competition.

From watching Neal’s AoC videos, I’m guessing the fun part for top CP’ers is speedforcing these problems. But personally, these problems aren’t even fun to speedforce, because they’re so overly tedious and verbose with almost no slick observations needed, making it quite literally a reading comprehension and typing contest. I guess the one cool thing coming out of this was that I got slightly more proficient at Python. I decided since the format of this contest was “submit output only,” I would use Python and try to write as clean code as possible. I must say, some tasks like day 18 are much easier to handle with Python due to their input format, and I felt badass whenever I successfully used list comprehension to write one liners in certain probelms. All in all, the concept of Advent of Code is neat, but the problems just aren’t my type, and that’s perfectly ok.

A Practice Story

Since this post is already getting overly long and rambly, I’ll wrap it up soon and conclude with a short story about a problem I recently solved in practice. I found the process of solving this problem amusing because it ended up being a lesson in debugging and hashing out the details.

The Story

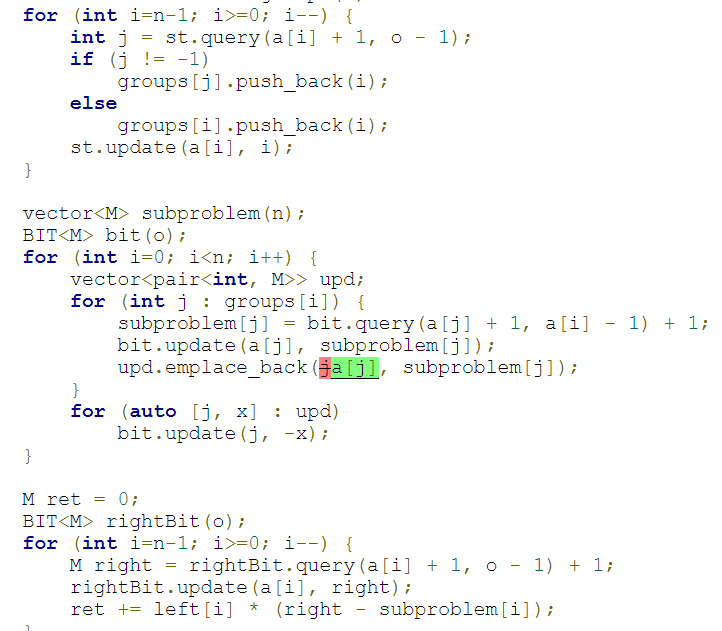

So I was solving this Codeforces problem that I pulled from this hard problem list. The problem didn’t seem too bad on first read, and I got most of the details for the solution right off the bat.

- Putting non-zero flow through each edge with $g_i = 1$ can be done by finding any arbitrary path of $g_i = 1$ edges from the source to the sink going through that edge and adding 1 to the flow of each edge on the path.

- To minimize the number of saturated edges, it suffices to only saturate edges in the minimum cut. This ensures any path from the source to the sink contains at least one saturated edge and thus no more flow can be pushed. To avoid including $g_i = 0$ edges in the minimum cut, my first idea was to just remove them from the network, which is incorrect.

I code up this idea, submit it, and am greeted with a wrong answer on test 3. I realize that my initial idea of excluding $g_i = 0$ edges from the network was wrong, because then it’s possible that there exists a path of mostly $g_i = 0$ edges and one unsaturated $g_i = 1$ edge from the source to the sink. Luckily, this issue is quickly remedied by adding the $g_i = 0$ edges to the flow network with capacity $\infty$ so that they won’t be included in the minimum cut.

However, after fixing what I thought was the bug, I still got wrong answer on test 3. Now I’m slightly confused. After rehashing through my idea and looking at all the details, I can’t see anything wrong with the idea. I figured it must be a bug with my DFS. I try reimplementing the same procedure with different variations and make multiple submissions, all succumbing to the same wrong answer on test 3. And after almost an hour, I finally cave and begrudging turn to external resources. I decided since I felt so close to the AC idea, I didn’t want to look at the editorial yet and just wanted a hint, so I scrolled through the comment section of the announcements blog. And I found my answer in this thread.

Ah, the devil is in the details! The nuance I was missing was that I didn’t properly consider reverse edges. I’d forgotten that part of what makes the flow algorithm work is that augmenting paths can travel through reverse edges and “cancel” out flow. If I include a $g_i = 1$ edge going backwards from the $T$-side to $S$-side, it’s possible for me to still have an augmenting path by going through a bunch of unsaturated edges from the source, going through that backwards $g_i = 1$ edge in reverse and cancelling out the flow already in it, and then going through more unsaturated edges to reach the sink. Luckily, the fix for this is simple: for each $g_i = 1$ edge, set the reverse capacity to $\infty$ so that the edge is never included backwards in the minimum cut.

Now here’s the kicker: my solution is still wrong! And still on wrong answer on test 3! I continue to make more tweaks and trying alternative ways of implementing the same thing. For example, I tried accounting for $g_i = 1$ edges in cycles by sending a unit of flow through the cycle it’s contained in instead of through a path from source to sink. All submissions succumb to the same wrong answer. And then, it hits me. My clown ass was finding the minimum cut wrong! In my DFS method for finding the minimum cut, I wasn’t considering reverse edges in the flow network. Heck, I wasn’t even considering $g_i = 0$ edges in my DFS because it was the same DFS method that I never changed since my first submission! This is so spectacularly wrong that it’s a miracle my solution even passed test 2. I fix my DFS method and finally claim my AC.

My submission history after this fiasco…

Where was I going with this story? I’m not sure. I just felt like writing about it. I guess my biggest takeaways are:

- Fully understand the nuances of the algorithm you’re tweaking. I usually black box maximum flow, so this was a cool problem that had me better understand how flow worked.

- When debugging, actually debug. Look at all parts of the code, even parts you’re sure are right.

I’m not sure what the future of this blog will be. It’ll probably be a while until I write another long tutorial because those take time. Maybe I’ll get around to finishing that tier list. In any case, thanks for reading!

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops