2022 ICPC North American Championship

Yay the blog has been revived!

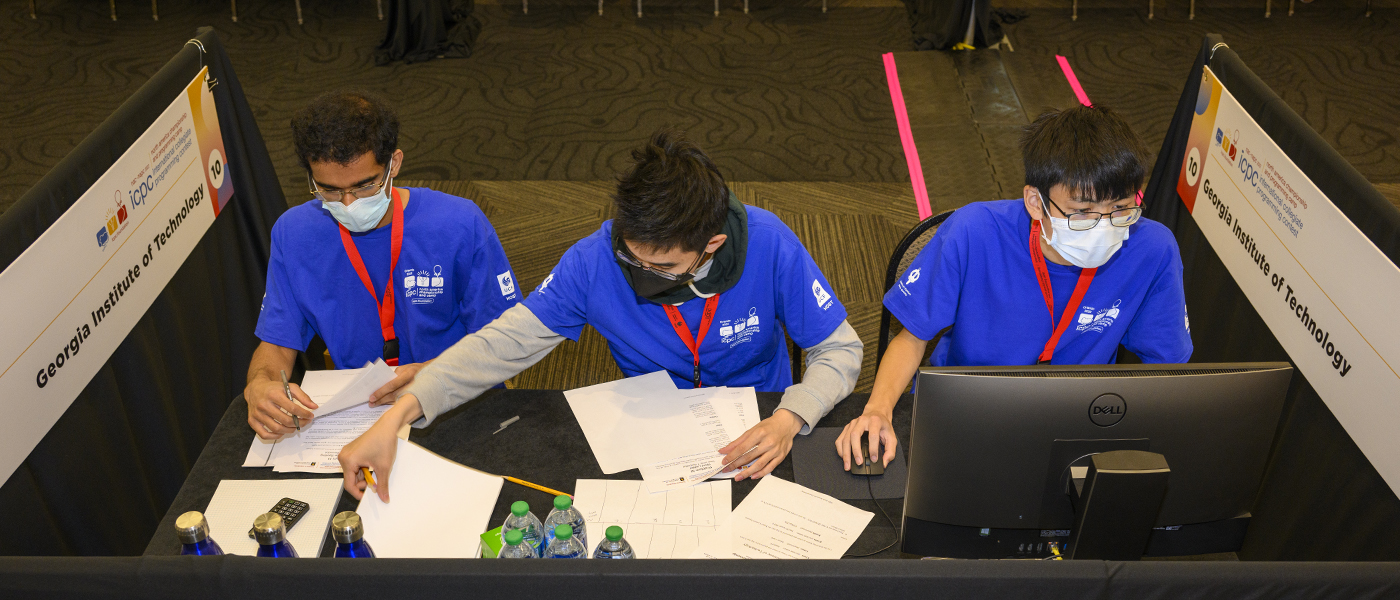

Hey everyone! This past weekend, I attended the 2022 ICPC North American Championship, which might just be the most fun CP in person events I’ve attended so far. I represented Georgia Tech alongside fellow teammates Arvind and Jeffrey. We got to fly down to Florida, meet CP people in person, and get all expenses paid for by our school! Literally the perfect formula for fun. In a similar spirit to my post about ICPC regionals, I’d like to write about my first ever NAC experience.

The next few sections will be me talking about the competitive programming aspects of NAC. If you don’t care for that, you can just scroll to the bottom where I talk about more social aspects and dumped some photos.

Expectations

If you take a look at the NAC teams list this year, you might notice that there are some really stacked teams this year. Over a dozen teams have at least one red person, some of which are IGMs, and many of them have done ICPC before and are therefore probably more consistent than us. Thus, our goal going in was simple: secure a spot in the world finals.

It’s a little hard to predict how many world finals slots there will be, because there are only two data points to go off of (2020 and 2021). Last year they cleared 19 teams, but I’ve been told that isn’t/won’t be the norm. The year before, it seems 17 teams were chosen, but it wasn’t simply just the top 17 teams on the NAC leaderboard. I found a list of the different criteria used to select teams that year, and it seems there were regional considerations as well. In particular, the maximum length prefix of teams on the leaderboard that all qualled in 2020 was only 10. So to secure a world finals spot, one would guess you want to be in the top 10, maybe 10-12 range.

The Contest

I’ll say right now, competing on site is a very different feeling from doing a team practice in a random room. At the start, you wait outside the ballroom anxiously as they filter teams into the room one by one. When you walk in, they announce your school through the speakers. You walk across the enormous ballroom to find your seat as Imagine Dragons’ “Whatever It Takes” is blaring through the speakers. You sit down and immediately notice the countdown timer on the big screen, counting down mere minutes before the contest starts. Different speakers and sponsors come on stage to give words of inspiration or talk about career opportunities, but everything is a blur because you’re only fixated on that timer.

When the timer hits zero, everyone scrambles for the keyboard and the problem set. I hastily configure VS Code and type out our template as my teammates start reading the set. The contest has begun.

In similar fashion to my regionals post, I’ll put a play-by-play in spoilers reassembled from memory, the scoreboard, and the livestream. Don’t worry, I assure you I’ll be far less salty than last time.

Play-by-play

A link to all problems can be found here.

The first few minutes are all devoted to setting up the environment and combing through the problems. The first AC from MIT comes in at 9 minutes for problem J. Upon reading this, we flip to problem J. It’s literally just brute force, simulate tic-tac-toe. I go to code up a simple recursive brute force. Unfortunately, it gets wrong answer. Oops. Luckily, I realize the fix shortly after:

In problem J, you also have to detect when a state is unreachable and print $-1$ in those cases. I handled most of the cases correctly but missed one: if the board has $3$ X tokens and $3$ O tokens, and X has $3$ in a row while O does not, then this is actually impossible. This is because X goes first, and after X wins, the game immediately ends, so it would have been impossible for O to place a third token. After correctly accounting for those types of cases, we get our first AC at the 38 minute mark.

The next problem we get AC on is M. Jeffrey comes up with a construction based on breaking a length 10 string into 3 sections and cycling AAAA -> AAAB -> AABB -> … That one fortunately gets AC first try at 56 minutes.

After that, Arvind attempts a solution for E. It unfortunately gets wrong answer. Arvind and I go to debug that solution while Jeffrey independently codes problem A. The next hour is pretty dry as both our A and E are wrong for the longest time. After a few bugs, we finally get AC on problem A 1 hr and 59 minutes in.

Unfortunately, the issue with problem E ran more deep than a simple implementation bug. Our initial idea was to let $dp[u][v]$ denote the minimum cost of making the subtree rooted at node $u$ valid and having its value be $v$. That formulation is fine. The problem was that we assumed $v$ would be bounded by some constant multiple of $100$, because the input values were bounded by $100$, and we used that assumption for a $\mathcal O(nv^2)$ solution. An upper bound on the total answer is of course $2n$ (by simply changing all node values to $2$), but maybe each individual value never needs to be that big in an optimal solution? Unfortunately, that’s not the case. A counterexample would be a root with $n - 1$ children, around half of which are $89$ and half of which are $97$. Then an optimal solution is to change the root to $89 \cdot 97 = 8633$. It took us a while and three wrong submissions to come to this conclusion…

Eventually, after realizing this, Arvind reformulates the DP to work for $v \leq 2n$, and we get to a $\mathcal O(n^2 \log n)$ solution from iterating over the prime divisors for the transition. After another wrong submit from a typo, we finally get AC on problem E.

At this point, we’re in a tricky spot. It’s 2 hours and 40 minutes into the contest, and we only have 4 problems and dubious penalty. 2 hours and 40 minutes for the 4 easiest problems in the set does not bode well for our ability to get the harder problems in time… I won’t lie, at this stage of the contest I was concerned we weren’t going to make it.

The next problem we solve is problem G. At this point, we were just chasing the scoreboard, and several problems (F, G, L) seemed roughly tied at this point. Problem G effectively gives us a functional graph and asks us to find a path on this graph visiting the most number of distinct sightseeing spots. The issue with a straightforward DP is accounting for overcount of sightseeing spots, so the best you could do with that idea is $\mathcal O((rc)^2)$ with reduced constant from bitset.

Fortunately, you can just reverse the edges, which gives you a tree rooted at either a single node or a cycle. And once you convert the problem to a tree problem, the rest of the solution flows quite naturally: DFS from the root and collect the sightseeing spots in some hashmap/frequency array for a pure $\mathcal O(rc)$ solution. There is a bit of code to hammer out to handle the 6 different types of characters in the grid and the contraction of cycles into single nodes in the tree, but it’s not too bad, and we’re able to get it with minimal dirt at the 3 hour 24 minute mark.

While I was implementing G, Jeffrey also read and worked out the solution to problem F, and he explains the solution to me after we AC G. The solution ends up being a clean $\mathcal O(nt \cdot 2^n)$ bitmask DP. We get AC on that problem just after the 4 hour mark.

We’re now in the final hour, and the scoreboard is frozen. We have 6 problems and still slightly dubious penalty. Maybe we’ll be ok if we don’t get one more, but it’s hard to say. The final problem we go for is L. L was a problem I read earlier because we saw MIT solved it ridiculously early and quickly, but I dismissed it because at the time I didn’t even know how to solve it in 1D, let alone 2D. But the trick to the problem actually turns out to be quite simple (courtesy of Arvind): if you have too many points in your rectangle, then the answer is always 1. There will always be some triplet $(a, b, c)$ such that $a \leq b \leq c, a + b > c$. Specifically, the worst case grows like the Fibonacci sequence ${1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, \dots}$. So if you just set a threshold of $45$ points, then you can always print 1 if there are more than that many points in the rectangle, and use brute force otherwise.

The cleanest way enumerate all the points in a rectangle is with a merge sort tree, where you descend on the segment tree for the first dimension and binary search in a sorted vector for the second. Unfortunately, I kind of forgot that existed during the contest, so I thought you needed something more complex like a raw 2D segment tree with pointers and whatnot. Raw 2D segment tree is notorious for using a ton of memory, and it has been forever since I last implemented one, so I wasn’t confident in my ability to code one. Fortunately, I also realized you can do square root decomposition instead. Just partition the first dimension into blocks containing sorted vectors and binary search on the second dimension. Funny enough, this is just a strictly worse version of the optimal segtree + sorted vector approach, so I’m not sure how I didn’t think of that after thinking of square root, but whatever.

I go to implement this solution, and after getting a RTE due to setting incorrect array bounds, I get a WA still. Uh oh. But we remain calm. There’s still like 40 minutes left. As long as we debug like we always do, it’s literally impossible for us to not get such a raw DS problem before the contest ends. Also, since this is the last problem we plan on ACing, Arvind and Jeffrey had already created small cases to try while I was implementing, so we had plenty to go off of.

And fortunately, we do get it. I manage to find my typo after combing through my printed code. And after fixing, submitting, and anxiously waiting, we get our AC verdict! This is it! We’re at 7 problems! We should be clean!

As a bonus, we also thought we might have gotten the solution to problem I near the very end as well, but we did not finish implementing in time. We also decided to spam submits on every problem at the last minute for fun, since the scoreboard was frozen and it would show a million question marks, but we could only get submits in on problems B and I before we got rate limited lmao.

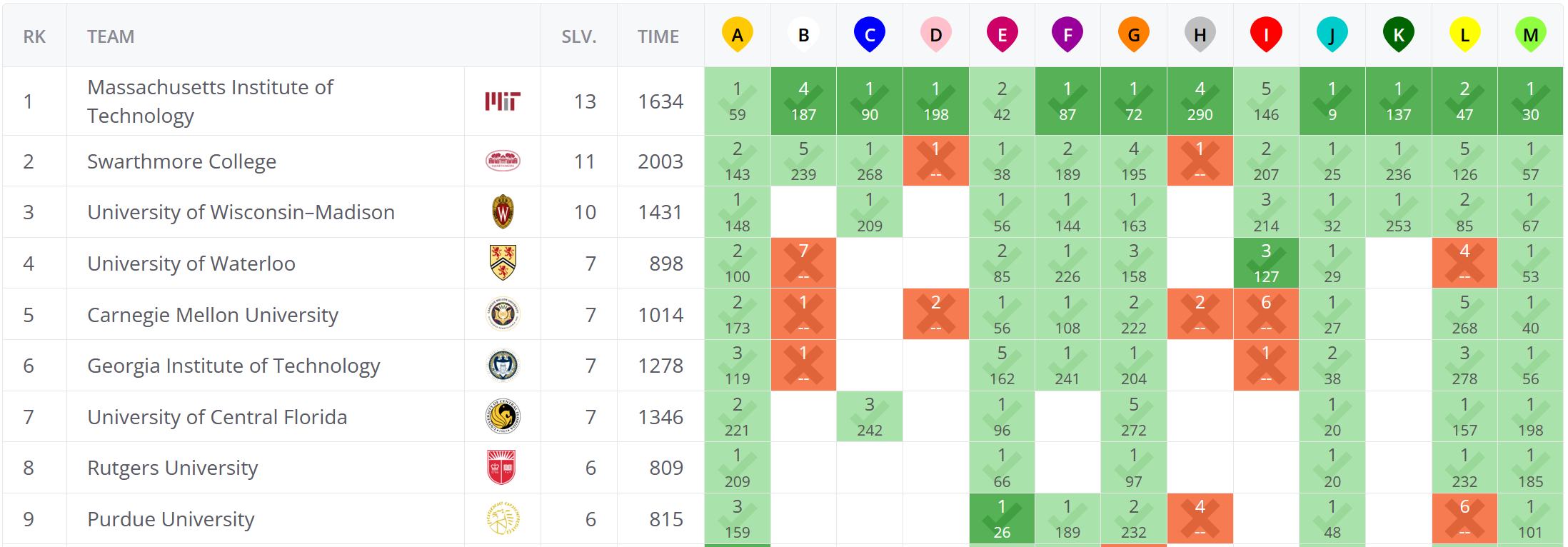

Ultimately, we ended up solving 7 problems, which we were almost certain coming out of the contest was enough to qualify for world finals! And after asking around and finding out that a lot of teams were actually at 6, we realized we might medal too!

The Results

Resolving the scoreboard one-by-one is genius.

I must say, that was a very anxious closing ceremony to sit through. But after listening to some long speeches and going through the awards for the NSA challenge and first solves, we finally get to the real deal. They announce there will only be 6 medals. Oh dear. That’s going to be tight then, because we’ve already identified that some teams who would have better penalty than us if they were on 71. How many teams will actually hit 7 though?

It turns out, few enough that we’re perfectly 6th! I just remember being so ecstatic upon finding out. The commitment to ICPC at the start of this year and the practices we did were all worth it. The effort was worth it. There’s no feeling more rewarding than that.

From left to right: Jingbang (coach), Arvind, Jeffrey, Me

The Experience

There’s a bigger group pic out there that exists but I have yet to get my hands on it.

Omg who dis

Regardless of the results, this was already one of the best competitive programming experiences I’ve had so far. There’s something surreal about meeting someone who you only knew by their handle previously, but now have a real name and face to match it to. There’s something surreal about chatting with others about CP in real life. Like you’ll mention a Codeforces round or blog, and others will actually know what you’re talking about. Heck, there’s something surreal about finding out there are people who actually read this blog!

I also found out I suck at Poker. And Secret Hitler. And lockout. Luckily (or unfortunately), I have like a year2 to get better at all of these before world finals 😅

But with that, I think I will end it here. I originally had a whole other section about NAPC, the programming camp that happens before NAC, but that section ended up being too rambly and not going anywhere. I want to keep this post shortened to just the highlights and my main thoughts.

Also, as a reward for making it this far, I have a sneak peak for my next educational blog that will be crossposted to Codeforces: click me! So stay tuned for that.

-

Specifically, Jeffrey spent like the entire time in between the contest and the closing ceremony asking around and figuring out which teams were on 6 or 7 solves, and ended up narrowing it down to confirmed 6th or 7th, depending on whether or not the University of Washington solved 7 problems. ↩

-

I heard rumors 2022 world finals will be in November 2023? I also heard it will be in Egypt? Or Budapest? Who knows. ↩

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops