Maintaining a CP Library

I love maintaining a competitive programming library. You get to implement things attuned to your own personal style, and it’s super satisfying when you use something from your library to successfully pass a problem. There’s also just something satisfying about working on a project over a long period of time, and having it grow and evolve alongside your CP journey. I started my library 3 years ago1 in high school, and it’s come a long way since then. And so now, I write this article so that I can plug my library explain how I design my implementations and how they integrate into my setup.

Coding Style

The main reason I maintain a library is to have templates that integrate with my coding style. In CP, my code usually follows these certain guidelines:

- I don’t use global variables. Instead, everything is in the main method, and I use lambda functions to substitute normal functions. This way, I don’t ever worry about not resetting global variables in between test cases.

- I use vectors over C-style arrays so that out-of-bounds errors are caught earlier in samples rather than later in large tests.

To abide by these guidelines, you’ll notice that my templates are usually in self-contained structs 2, so that I can declare a new instance of them per test case.

An Example

Here’s an example of a template for strongly connected components:

Click Me!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

// https://github.com/mzhang2021/cp-library/blob/master/implementations/graphs/SCC.h

struct SCC {

int n, ti;

vector<int> num, id, stk;

vector<vector<int>> adj, dag, comp;

SCC(int _n) : n(_n), ti(0), num(n), id(n, -1), adj(n) {}

void addEdge(int u, int v) {

adj[u].push_back(v);

}

void init() {

for (int u=0; u<n; u++)

if (!num[u])

dfs(u);

dag.resize(comp.size());

for (auto &c : comp)

for (int u : c)

for (int v : adj[u])

if (id[u] != id[v])

dag[id[u]].push_back(id[v]);

for (auto &v : dag) {

sort(v.begin(), v.end());

v.erase(unique(v.begin(), v.end()), v.end());

}

}

int dfs(int u) {

int low = num[u] = ++ti;

stk.push_back(u);

for (int v : adj[u]) {

if (!num[v])

low = min(low, dfs(v));

else if (id[v] == -1)

low = min(low, num[v]);

}

if (low == num[u]) {

comp.emplace_back();

do {

id[stk.back()] = (int) comp.size() - 1;

comp.back().push_back(stk.back());

stk.pop_back();

} while (comp.back().back() != u);

}

return low;

}

};

The way you use this template is quite straightforward: you declare an instance of SCC initialized with the number of nodes. You add each edge with the addEdge() method. When you’re done adding edges, you call init(), and afterwards comp will be populated with the nodes partitioned based on strongly connected components, and dag will be an adjacency list for the condensation graph. Importantly, I don’t have to remember how the SCC algorithm actually works. I can just paste it in my global scope, then use it as a black box for solving a problem.

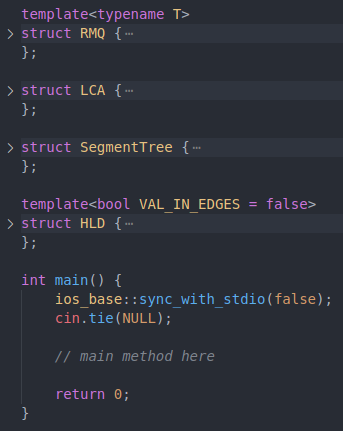

More generally, packing templates into structs like this makes life easier if I have to use multiple templates. For instance, my source file for a implementation-heavy tree problem might look something like this:

Pretty clean if you ask me.

How Generic Should Templates Be?

This is something that I’ve gone back and forth on. Should I have to modify the internals of my implementation, or should I be able to abstract away the details and use it like an external library? The philosophy I’ve gone by is to try to make it as generic as possible, without making it too clunky or unnatural. For example, the following is a template for sliding window minimum/maximum:

Click Me!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

// https://github.com/mzhang2021/cp-library/blob/master/implementations/data-structures/MinDeque.h

template<typename T>

struct MinDeque {

int l = 0, r = 0;

deque<pair<T, int>> dq;

void push(T x) {

while (!dq.empty() && x <= dq.back().first)

dq.pop_back();

dq.emplace_back(x, r++);

}

void pop() {

assert(l < r);

if (dq.front().second == l++)

dq.pop_front();

}

T min() {

assert(!dq.empty());

return dq.front().first;

}

};

This is an implementation that’s easy to make generic. The following code will work for any data type with comparison defined. On the other hand, lazy segment tree is something that’s notoriously difficult to make generic. Here’s my variant of lazy segment tree:

Click Me!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

// https://github.com/mzhang2021/cp-library/blob/master/implementations/data-structures/SegmentTreeNodeLazy.h

struct SegmentTree {

struct Node {

int ans = 0, lazy = 0, l, r;

void leaf(int val) {

ans += val;

}

void pull(const Node &a, const Node &b) {

ans = a.ans + b.ans;

}

void push(int val) {

lazy += val;

}

void apply() {

ans += (r - l + 1) * lazy;

lazy = 0;

}

};

int n;

vector<int> a;

vector<Node> st;

SegmentTree(int _n) : n(_n), a(n), st(4*n) {

build(1, 0, n-1);

}

SegmentTree(const vector<int> &_a) : n((int) _a.size()), a(_a), st(4*n) {

build(1, 0, n-1);

}

void build(int p, int l, int r) {

st[p].l = l;

st[p].r = r;

if (l == r) {

st[p].leaf(a[l]);

return;

}

int m = (l + r) / 2;

build(2*p, l, m);

build(2*p+1, m+1, r);

st[p].pull(st[2*p], st[2*p+1]);

}

void push(int p) {

if (st[p].lazy) {

if (st[p].l != st[p].r) {

st[2*p].push(st[p].lazy);

st[2*p+1].push(st[p].lazy);

}

st[p].apply();

}

}

Node query(int p, int i, int j) {

push(p);

if (st[p].l == i && st[p].r == j)

return st[p];

int m = (st[p].l + st[p].r) / 2;

if (j <= m)

return query(2*p, i, j);

else if (i > m)

return query(2*p+1, i, j);

Node ret, ls = query(2*p, i, m), rs = query(2*p+1, m+1, j);

ret.pull(ls, rs);

return ret;

}

int query(int i, int j) {

return query(1, i, j).ans;

}

void update(int p, int i, int j, int val) {

if (st[p].l == i && st[p].r == j) {

st[p].push(val);

push(p);

return;

}

push(p);

int m = (st[p].l + st[p].r) / 2;

if (j <= m) {

update(2*p, i, j, val);

push(2*p+1);

} else if (i > m) {

push(2*p);

update(2*p+1, i, j, val);

} else {

update(2*p, i, m, val);

update(2*p+1, m+1, j, val);

}

st[p].pull(st[2*p], st[2*p+1]);

}

void update(int i, int j, int val) {

update(1, i, j, val);

}

};

To use this for a general problem, I’d have to modify the Node class, the returned parameter of query(), and maybe the push() method if I modify the lazy parameter. So that’s quite a bit of internals that I have to mess with, although I think I prefer this to fully generic attempts at lazy segment tree. For contrast, the Atcoder Library has a fully generic variant of lazy segment tree, and it ends up being kind of clunky because you have to define a struct for the data and lazy values, and define functions for interactions between them. Ultimately, it’s up to personal preference, and I just think it’s easier to not bother trying to make a lazy segment tree fully generic.

Does It Always Make Sense to Use Structs?

Consider something like combinatoric functions (factorial, choose function, etc.). Currently, I have the following template for it:

Click Me!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

// https://github.com/mzhang2021/cp-library/blob/master/implementations/math/Combo.h

#include "Modular.h"

using M = ModInt<998244353>;

const int MAX = 1e5 + 5;

M fact[MAX], inv[MAX];

M choose(int n, int k) {

if (k < 0 || n < k) return 0;

return fact[n] * inv[k] * inv[n-k];

}

void preprocess() {

fact[0] = 1;

for (int i=1; i<MAX; i++)

fact[i] = fact[i-1] * i;

inv[MAX-1] = inverse(fact[MAX-1]);

for (int i=MAX-2; i>=0; i--)

inv[i] = inv[i+1] * (i + 1);

}

In this case, it doesn’t make much sense to wrap it in a struct, because these things values are usually precomputed once for the entire instance of execution, not once for each test case. And since it’s not really a data structure, it would be strange to treat it as one by wrapping it around a struct. Right now, I just put this in the global scope, but this does violate my guidelines by creating global variables fact and inv. One alternative that I’ve considered, which I’ve seen others do, is use namespaces. While I could, I’ve decided namespaces aren’t worth the effort, because in practice I’ll do using namespace template_name; anyways, and then it’ll effectively be global variables anyways. I guess it could provide an extra layer of organization, since I can minimize namespaces in my IDE, but that’s not too big of a deal.

Where to Test Templates?

In order of preference:

- Yosupo Library Checker - This has a wide array of well-known problems, and test cases are added by community members, so you can be pretty confident in their strength and coverage.

- CSES - Similar to Yosupo Library Checker, has a lot of well-known problems and test cases are added by community members.

- Problems from Various OJs (Codeforces, etc.) - Codeforces does have hacks, but there’s no guarantee a contestant added such a hack back when the contest was live, and there have certainly been instances of Codeforces problems with weak test cases. Other online judges don’t even support hacks. And it can be harder to find a problem that tests for a specific template.

Is Building a Personal Library Worth It?

It’s definitely not necessary. Plenty of people have gotten very far from copy pasting off KACTL. I just personally maintain a library because it’s fun, and it’s a tangible project I can point to and be proud of.

-

If you check the stats for my Github repo, it was created in February 2020, but that was only the date when I put my implementations on Github. Before then, I used to store them locally on my laptop like a bum. ↩

-

Some of my implementations use an outdated style like global arrays with fixed sizes. Those are usually implementations leftover from a long time ago that I never bothered to revamp because I don’t use them frequently enough. ↩

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops