What Makes a Problem Hard?

Just go to the comment section of any announcement blog for a contest, and you’ll likely see a comment like “A < C < B” or “E was much easier than D.” Or look at any leaderboard, and there’s always at least a few contestants who solve the problems out of order or skip some problem. Problem difficulty is a very subjective thing, and it’s always near impossible to create a set of problems such that A is strictly easier than B, which is strictly easier than C, and so on. Why is that the case, and what makes a problem difficult?

Knowledge

The difficulty of the algorithms and concepts used for a problem definitely contribute to problem difficulty. For instance, greedy is a very fundamental concept, and applying the “greedy” tag in Codeforces problemset yields problems of all difficulties from 800 to 3500. On the other hand, applying the “flows” tag quickly brings problems up to the 1800-2000+ range, and applying the “fft” tag almost guarantees the problem is at least 2000+ in rating, because of the complexity of these algorithms (at the time of writing this, there is an 800 problem marked with “flows”, but I am almost certain that is a troll).

Search Space

This aspect is one that I think gets overlooked the most when people claim a problem is too easy for its spot in a contest. When you approach a problem, there are a lot of ways you can go about it, and a lot of potential approaches to try. Not all approaches will lead to the solution. Take this problem for example. It’s a 2700 rated interactive problem. And if you’ve read the editorial or know the solution, you might conclude that the problem should be rated way lower because the solution is so elementary. But the difficulty of this problem doesn’t come the complexity of the concepts used, but the sheer size of its search space. I did this contest live, and I remember trying all sorts of different ways to take advantage of the $\lfloor \log_2{n} \rfloor$ bound in queries, some very close to the editorial idea.

Number of Observations/Steps

Partly related to search space is the number of layers of observation you have to get through to solve the problem. Div 2 As and Bs typically only have one key observation that cracks the entire problem, which is why they can be solved in mere minutes by high rated contestants and have low ratings (as an aside, an unfortunate consequence of these problems is that sometimes solving them can be dumb luck because of how unmotivated the observations can be, and even a high rated contestant could get “stuck” on one if they just happen to miss the observation). On the other hand, a more difficult problem often contains multiple layers of reduction to get to the final solution.

The example I’ll use is Falling Sand, which is a problem with several steps. In my opinion, each individual step is not difficult, but it can be difficult to assemble all of the necessary steps during a live contest. The solution breaks down as follows:

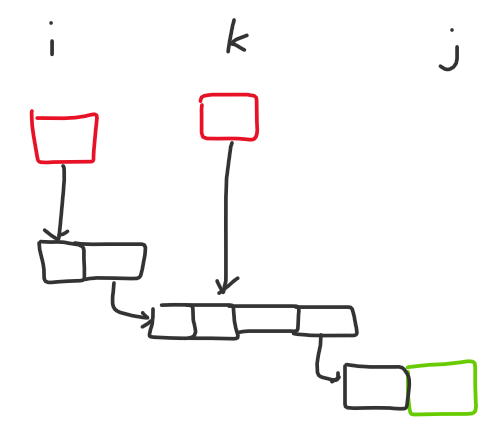

- Recognize that the relation between the blocks of sand can be modeled as a directed graph, where block A can reach block B if perturbing block A will cause it to perturb block B when falling.

- The directed graph actually only contains $\mathcal O(nm)$ edges, as it is sufficient to draw an edge from a block to the closest block below it in its adjacent columns.

- The above two observations are sufficient to solve F1. In F1, we just need to make all the sand blocks fall, so after compressing the graph into a DAG of SCCs, we can count the number of nodes with an indegree of 0 as our answer.

- In F2, we don't need to make all the sand blocks fall, just $a_i$ in each column. It is always optimal to prioritize making the bottommost $a_i$ blocks fall in each column $i$, as those blocks will always fall anyways in any optimal solution.

- Let's consider the set of nodes with indegree 0 in the DAG after condensing into SCCs, denoted as $S$. Obviously it is optimal to only perturb nodes in $S$ directly, because if we perturb some lower node, we could have perturbed one of its ancestors instead and achieved the same effect (yeah I know I'm using the words "node" and "block" interchangeably). Now let's consider the nodes that need to be perturbed. Notice that the subset of $S$ which can reach that node, directly or indirectly, are always contiguous if $S$ is sorted by column. If a node in column $i$ can reach our target node, and a node in column $j > i$ can also reach our target node, some node in $S$ in column $k$ such that $i < k < j$ would also be able to reach our target node.

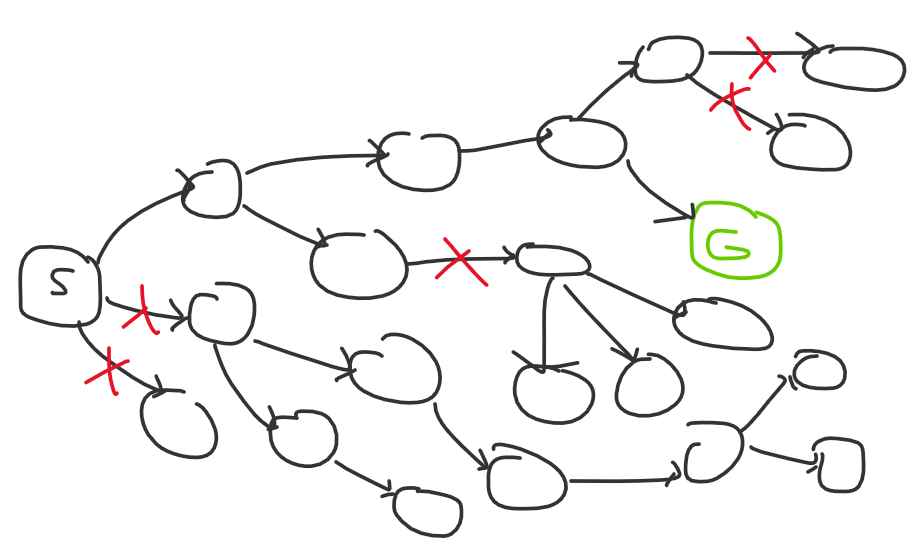

- To understand why that is true, notice that the structure of how blocks get perturbed is always "hit all blocks in this and adjacent columns," so there's a "path" of contiguous nodes from column $i$ to column $j$ for some node in column $i$ to be able to reach column $j$. Since the nodes in $S$ are always the highest nodes in their column, there's no way they would not be able to reach the "path" if they were in some column $k$ such that $i < k < j$. To understand what I'm talking about, refer to the diagram below (red blocks are in $S$, green is our target block):

- Therefore, the problem reduces down to picking the minimum number of nodes in $S$ to cover all intervals. This is a well known problem with a greedy solution: sort the intervals by right endpoint, and whenever an interval is not covered, increase the answer by 1 and pick the node on the interval's right endpoint.

Combining Search Space and Number of Observations

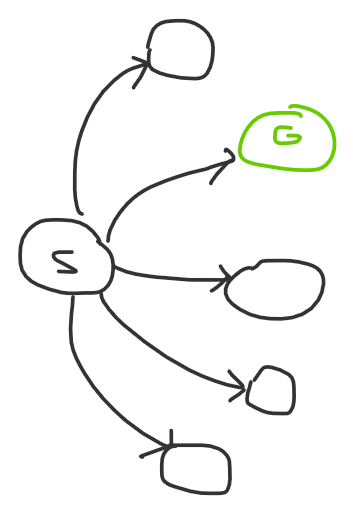

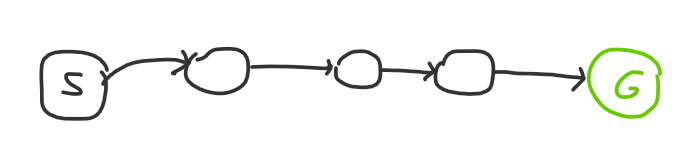

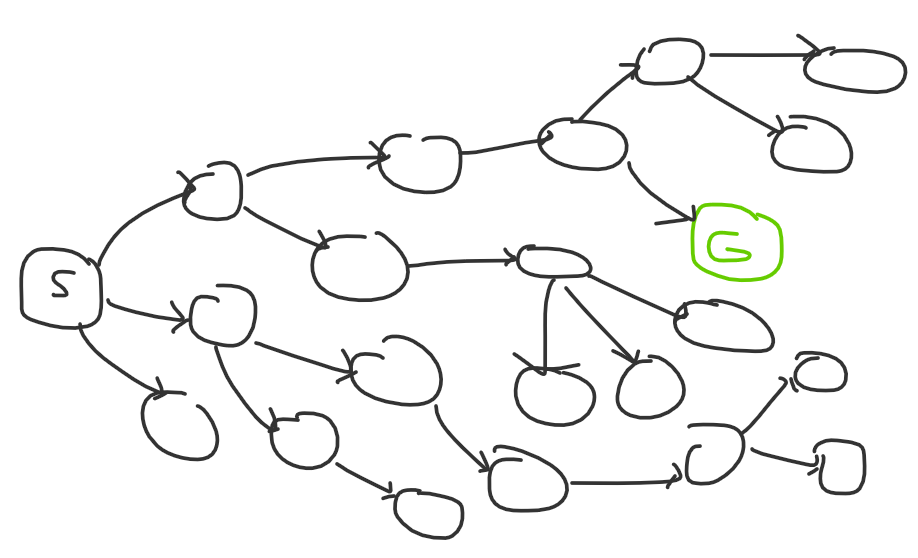

Let’s say the search space of a problem is a graph. You start at the beginning, and you want to reach the solution by traversing through a path of nodes by making a series of observations. Then a larger search space refers to larger degree nodes, and more observations means the path to the solution is longer. So an easy problem might look something like this:

or this:

The first diagram is what a Div 2 A might look like: there’s one observation, and if you find it you solve the problem. The second diagram is what an easy DS problem might look like: there might be multiple steps, but each step is very obvious to get to. Naturally, a hard problem both has high degree nodes and a long path:

If you’re a strong competitive programmer with lots of problem solving expertise, the problem search space might look more like this to you:

The red Xs are a result of experience: you know which ideas tend to work better, and you know how to approach certain types of problems.

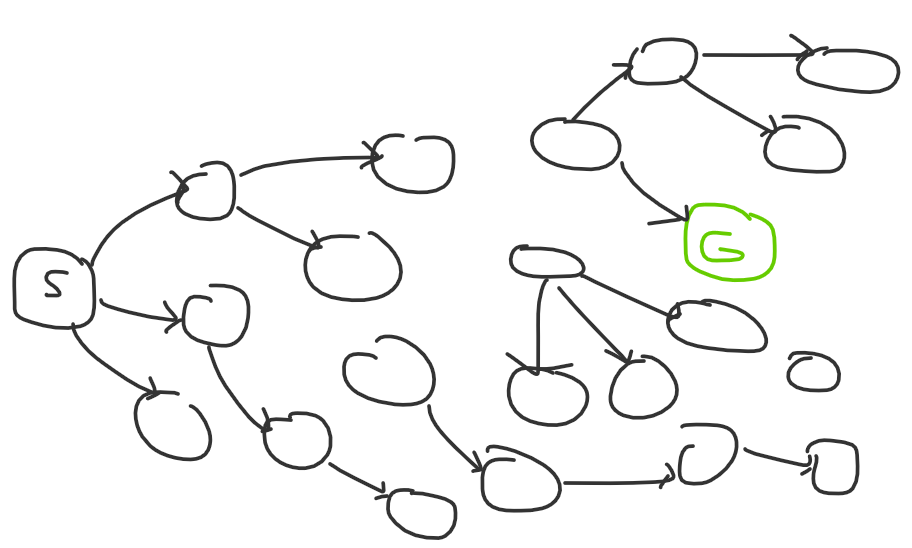

And to complete this analogy, if you’re missing knowledge or experience, the problem might look like this to you:

You’re missing edges altogether, so you might not even be able to solve the problem, but those edges will appear with practice and time.

Implementation

There’s one aspect of problem solving I have not mentioned yet: after coming up with the idea, you still need to write the code! So what makes implementation difficult?

- Lines of Code - When I say lines of code, I exclude templated code. Take Good Graph as an example. Most submissions have lines of code in 3 digits, but a large portion of this problem is just copy pasting heavy light decomposition or segment tree, so the actual difficulty of implementation is low. On the flip side, Binary Table was a problem with a notoriously long and difficult implementation for its spot in the contest. It’s not too bad for experienced contestants, but it’s definitely way more implementation heavy than a Div 1 A should be.

- Finnicky Details - I’ve encountered plenty of problems where working out the indexing was a pain in the ass, or the problem had many cases to consider. In recent memory, Minimax had an obnoxious amount of cases, and my implementation in contest ended up being extremely messy. It’s honestly a miracle that I could even get it to work at all. Funny Substrings was another problem where I had a disgusting implementation in contest that demanded a high attention to detail, although this one was more my fault for overlooking a simpler solution.

- Constant Factor Optimization - It’s always frustrating when you have the correct complexity, but your solution is too slow because of unnecessarily tight limits set by the authors. There are ways to minimize this happening by adopting certain strategies. For example, I always pass non-primitives by const reference to functions, and I avoid STL data structures when not needed because C++ STL data structures like

std::setandstd::mapconsume a non-trivial amount of overhead.

So back to the original question…

Different people have different opinions on problem difficulty because they’ve practiced and become more experienced in different skills. Each person’s graph for the search space will look different. And the problemsetter’s opinion of difficulty often differs drastically from competitors because they sometimes come up with the solution before the problem, or craft the problem with a specific solution in mind already.

The Takeaway

Is there a takeaway from this article? I don’t know. I’m moreso just expressing an opinion on a subject that I’ve given some thought about. That being said, I do think the way I think about problem solving provides some insight into how I think improving at CP works: as you practice, you expand the number of edges you can access, and you also get better at pruning bad edges. Maybe in the future I’ll write an article on how to practice. Thanks for reading, and feel free to leave your thoughts on this subject in the comments below.

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops