Burnside's Lemma

Disclaimer: I typed this up a few months prior to making this website as personal notes for myself, so it’s possible that the article may be unclear in certain sections. If you have any tips on making certain sections clearer, feel free to comment below.

Burnside’s lemma is a topic that’s often explained in a group theory context and in a very abstract manner. Here I will attempt to document a more intuitive explanation of the lemma.

Main Idea

Consider the following simple problem: Given a cube, if we color each face one of three colors, how many rotationally distinct colorings are there?

The condition of being rotationally distinct means we have to account for an intractable amount of cases. For example, what if the opposite sides are the same color? Or what if this subset of sides are the same color? The casework gets tedious very quickly, so Burnside’s Lemma helps us simplify that casework.

The statement of Burnside’s Lemma:

\[|\text{Classes}| = \frac{1}{|G|} \sum_{\pi \in G} I(\pi)\]That’s a very dense definition! In simple terms, we say the number of rotationally distinct colorings is equal to the average over all ways of transforming the object.

Wait what?

We use the example of a cube.

First, let’s say our cube is locked in place, we cannot rotate it in any way. The number of colorings is then $3^6$: we have $3$ choices of colors for each of the $6$ faces.

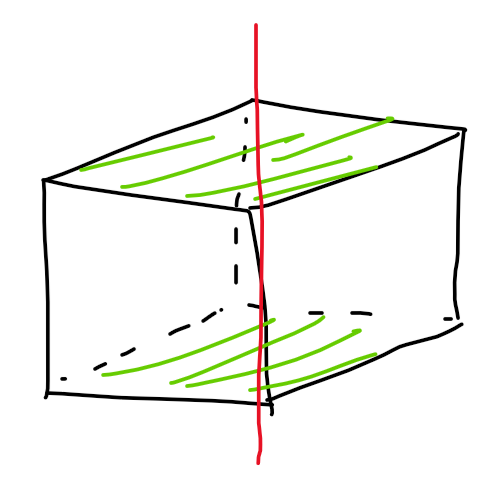

Now, let’s consider the next method of transformation: the cube rotates $90^\circ$ counterclockwise along the axis through the top and bottom face:

(It’s difficult to draw 3D on a 2D plane, so I’ve shaded the two faces the axis goes through in green)

Essentially, we want to count the number of colorings of this cube, where each coloring maps to itself via a single $90^\circ$ counterclockwise rotation about the red axis. I think these are called “fixed points.” Let’s say we color the front face blue. Note that this means in all colorings of this group, the right face must also be blue. Why? Because all colorings must be able to “reach” one another with the power of a single $90^\circ$ counterclockwise rotation. Applying this same argument repeatedly, we note that therefore all four lateral faces must be blue. So in total, there are $3^3$ distinct colorings for this group: one color for the top face, one color for the bottom face, and one color for all four lateral faces.

Let’s consider another transformation: a $90^\circ$ clockwise rotation about the red axis. This, as you might guess, is the exact same as the previous case, so we get $3^3$ colorings from this group.

Here’s a more interesting transformation: a $180^\circ$ rotation about the red axis (note I didn’t specify clockwise or counterclockwise since they’re the same). In this case, the front face must match the back face, but the front face need not match the right face, because there is no way to apply a $180^\circ$ rotation to map the front face onto where the right face would be. Thus, we have $3^4$ colorings for this group: top, bottom, left/right, and front/back.

We will continue these calculations with all transformative methods, with others such as rotating about the axis through the left and right face, or rotating about the axis through opposite corners. You can see all the calculations enumerated in this video. In total, there are $24$ different groups. The number of rotationally distinct colorings ends up being $57$.

Atcoder ABC 198F: Cube

Same problem as our cube coloring problem, but instead of colorings, we write numbers on each face such that they sum to a constant $S \leq 10^{18}$.

Applying Burnside’s Lemma will give us equations for which we have to count the number of solutions to. For example, $a + b + 4c = S$. Many methods of counting solutions to such an equation become intractable when $S$ is large or when we have many variables. A simple way is using matrix exponentiation: let $dp_S$ be the number of solutions to $a + b + 4c = S$. Using the inclusion-exclusion principle, we get the recurrence $dp_S = dp_{S-1} + dp_{S-1} + dp_{S-4} - dp_{S-2} - dp_{S-5} - dp_{S-5} + dp_{S-6}$. Essentially, we add all ways based on choosing $a, b, $ or $c$ as our next variable to increase by $1$. However, increasing $a$ by $1$, then $b$, versus increasing $b$ by $1$, then $a$, are equivalent, so we subtract out one occurrence of counting both $a$ and $b$ increasing by $1$. Then, we over-subtracted out increasing $a, b, c$ all by $1$, so we add that back. The complexity of our solution is thus $\mathcal O(\log S)$, ignoring constant factors.

Colored Beads on Necklace

Say we have a necklace with $N$ pearls, each which can be colored one of $M$ different colors. How many rotationally distinct colorings are there? This problem is the example used in the Competitive Programmer’s Handbook.

Our transformation possibilities are rotate $0$, rotate $1$, rotate $2$, $\dots$, rotate $n - 1$ beads clockwise. With no rotation, the number of ways is $M^N$. With one rotation, we reduce it down to just $M$ ways, since each bead must share the same color as the next. With rotating by $2$, we have $M^2$ ways because all beads at even positions must share a color, and all beads at odd positions must share a color, but there is no relation between beads of different parity positions. In general, if we rotate by $k$, we have $M^{\gcd(k, N)}$ ways.

To prove this, we essentially want to count the number of unique values of $(i + kp) \mod N$ for all positions $0 \leq i < N$ and $p \geq 0$. Let’s find the minimum $p$ until the position maps back to itself (i.e. $kp = 0 \mod N$), which happens when $p = N / \gcd(k, N)$. One way of thinking about this is that $k$ already contains some part of the prime factorization of $N$, namely $\gcd(k, N)$, and we need the other part of the factorization present in $p$. So if each component is of size $N / \gcd(k, N)$, then we have $N / (N / \gcd(k, N)) = \gcd(k, N)$ components.

Thus, our answer is

\[\frac{1}{N} \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} M^{\gcd(k, N)}\]Colored Beads on Necklace with Reflection

Same problem as previous, but now two necklaces are also identical if we allow reflections alongside rotations.

To make sure we’re not accidentally counting the same transformation twice, we always reflect over the horizontal axis first, then rotate. So we have $2N$ different transformations. And when I reflect, that means positions $i$ and $N - i$ map onto each other, assuming zero-based indexing. There isn’t an easy closed-form way of expressing this, but we don’t have to use a closed form. If we use DSU to merge together indices that map onto each other after the transformation, we can just count the number of components at the end. So this actually gives an algorithmic way of counting the fixed points, which is easily generalized to other problems!

By the way, there is a closed form of expressing this. First, we add up $\sum_{k=0}^{N-1} M^{\gcd(k, N)}$ to account for rotation without reflection. Now for reflection, instead of reflecting and then rotating, we can just rotate the reflection axis itself. For odd $N$, we have $N$ choices of a reflection axis, where each goes through exactly one bead and the center of the circle, giving us $M^{N/2 + 1}$ ways to color ($N / 2$ pairs formed over the reflection axis, plus $1$ for the single bead that we initially chose). For even $N$, we have $N / 2$ reflection axes that go through two beads, and $N / 2$ reflection axes that go through no beads but are instead in between beads, giving us $N / 2 \cdot M^{N / 2 + 1} + N / 2 \cdot M^{N / 2}$ ways. Finally, we divide our total by $2N$ to get our answer.

References

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6kfbotHL0fs

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops

Subscribe to receive notifications when a new post drops